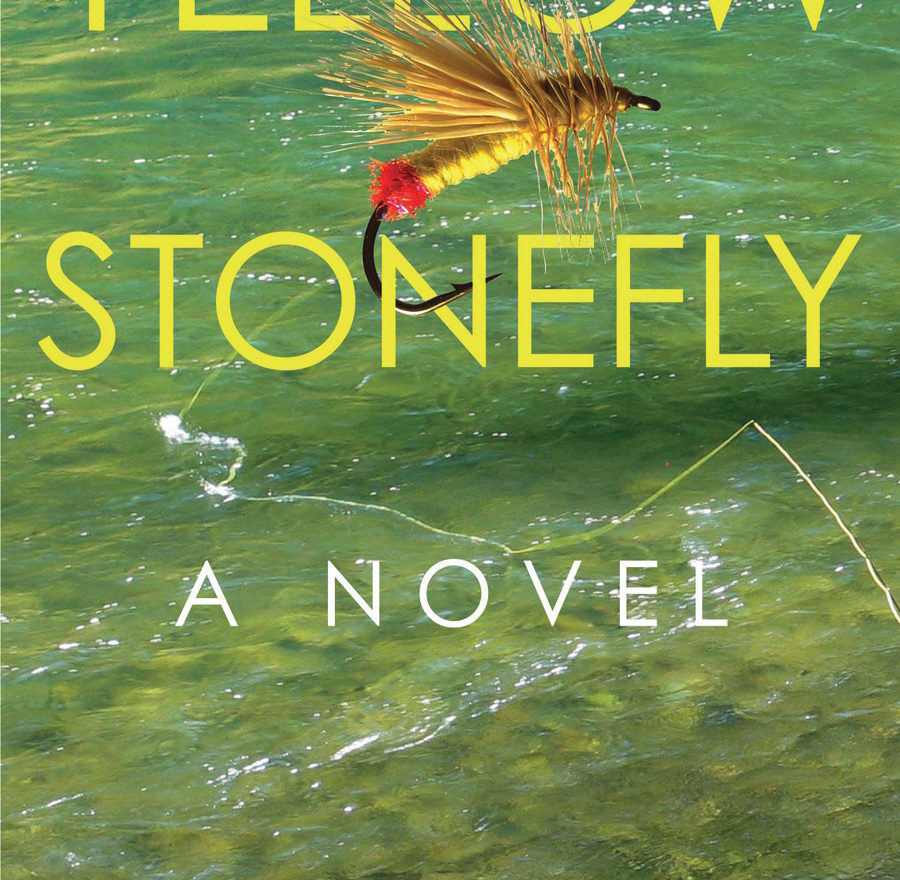

Excerpted with permission from Tim Poland’s latest novel, “Yellow Stonefly”

Though the sun was well behind the ridge, there remained more than enough light filtering through the newly leafing trees, and the cooling air still held much of the day’s warmth.

Book cover image courtesy Tim Poland

The stone-fly hatch was largely spent. Here and there, a few stragglers remained on exposed rocks or flitted through the air around Sandy, their tiny yellow bodies floating within the blur of their four translucent wings. She’d made it just in time to cast her simulated yellow stonefly into the dissipating flurry of real stoneflies. The trout would still be stirred up.

Sandy moved from her observation blind behind one of the larger boulders along the stream and stepped in a half crouch into the shallower water at the edge of the pool. She waded in with a seamless grace her gait could never match on land, barely stirring the water from its natural course. Stripping only a few feet of line from her rod, all that was required, she targeted the back of the pool. A single slight flick of her wrist set the line in motion and dropped her fly on the tongue of current feeding into the tail of the pool. The tiny yellow fly rode the surface of the water for barely a second before the fish hit it. As brook trout will do, the fish took the fly hard and fought fiercely. Time and familiarity had not diminished Sandy’s awe and respect for these small creatures. This degree of ferocity in a larger species of trout could have snapped her line handily, and Sandy never forgot that. Her rod bowed in a deep arc, and Sandy held it high, leading the scrappy fish quickly but smoothly into the shallower water around her legs. Cupping the fish in her hand, she slid her hook from the trout’s bony upper lip. Its speckled back glistened a deep blue-green across her wet palm; the bright orange of its abdomen and ivory-tipped belly fins would be brighter still during the fall spawning season. Sandy released the fish back into the stream, where it disappeared instantly into the safety of deeper water.

The pool was alive and responsive. This she had learned, yet she limited her disturbance to the tail of the pool. Now she could move to the head of the pool, to the churning chute of water pouring in from the pool above, to the swirling back eddies under the overhanging rock ledges where the bigger fish waited.

Slowly, cautiously, keeping to the left of the current, she waded to- ward the head of the pool and set her sights on the back eddy to the right of the chute. The rushing water cut through the opening and fanned out through the pool. The back eddy formed behind the more agitated water. Beneath a huge hump of stone that bent to the water, the back eddy swirled around a circle of calmer water where a brook trout could hold outside the main current, saving its energy, protected by the ledge of rock above, while the river brought food to it. That small circle of water was Sandy’s target. Here the bigger fish would be. She’d taken fish in this pool many times, but getting them out of the back eddy was always tricky. She’d have only one chance.

Gauging the distance across the seam of current, she fed a little more line from her reel. Success would count on two things. She would need to bounce the yellow stonefly off the rock hanging over the eddy, to make it act like an insect that had bumbled from its perch into the water. That she could do easily. The harder task would be to keep her line from collapsing into the current between her and the eddy, which would then jerk her fly suddenly downstream, startling her prey and sending it so deeply into hiding under the rock ledge that she’d never entice it back out today. Her gaze turned for a moment up the slope, following the cascading course of the stream from pool to pool, through forest and stone. In her enlivened flesh she felt the implacable heft of centuries that lifted these mountains and forged them into this watershed, spilling the rush of time and water down into this pool where she stalked her prey. She had learned the language of trout. She could speak with the waters of this pool, and the fish it held, in a tongue intelligible in the wild world of water and stone. Here, on this evening, she spoke fluently. Rod and arm, like a single thing, held high over the slicing current, she shot her fly out to the rock overhanging the eddy. It bounced from the stone and dropped into the eddy, barely disturbing the surface. The fly sat the surface of the eddy, hardly moving. For a moment it shone forth, a shimmering dot of blazing yellow on the dark, still water, before the fish struck.

Under the throbbing bow of her rod, the brook trout spun and dove into the depths of the pool under the churning current. The tension in her arm hummed with the song in her tight line as she knelt in the shallows and drew the fish to her. Freeing the hook from its lip, she cupped the big brook trout in her hand for only a moment, relishing the weight of this native fish that draped well over both sides of her palm. Among the descendants of the brown and rainbow trout stocked in the controlled waters of the lower Ripshin, a fish of this size would be typical, worthy of no special note. Here in the wild reaches of the Ripshin’s headwaters, an indigenous brook trout such as this one was a prize beyond account. The fish slid smoothly from Sandy’s hand, held for a moment to collect its senses, then vanished into the depths of the pool, in search of its haven under the hump of stone.

Sandy shook the water from her hand and reeled in her line. She’d arrived in time for the yellow stonefly hatch and made the most of it. The well-made fly had told the story it was intended to tell, and she had delivered the tale well. It was enough for the day. The late afternoon light in the ravine was growing dim. She waded around the tail of the pool, stepped out to the footpath, and followed the path a few yards to a break in the rhododendron. Ducking through the opening, she climbed up the embankment to where the fire road cut out of the forest and curved along the riverbed at this point. It was time to find Keefe. Sandy turned downstream.

A few hundred yards down the fire road it didn’t surprise Sandy to find Keefe at the old Rasnake homestead. Old-timers in the valley called it that, and so did Keefe on occasion. Up a slight rise from the fire road, the dense trees opened out into a clearing. In the clearing were the tottering remains of three fieldstone chimneys, all that remained of three humble cabins that housed the extended Rasnake family when they first moved into the valley after the government ran the Cherokee out. The clearing was a regular retreat for Keefe, and Sandy found him there often, especially late in the afternoon when the sun had dropped behind the ridge. Keefe’s rod leaned against one of the old chimneys, and he sat on the worn hearth- stone, now caked with moss. He stared straight ahead at the other two chimneys across the clearing, his elbows on his knees, his hands hanging limp between his legs. He appeared startled when she walked up into the clearing, but immediately his face relaxed and he sat up from his slump and greeted her with the angler’s standard salutation. “Do any good?”

“Little bit,” Sandy replied, the angler’s standard response.

Keefe looked up at her from under the brim of his battered brown fedora, a grin dimpling into his face.

“That answer may be adequate for some other fool you meet on the stream. I think I merit a bit more detail, my dear.”

Sandy smiled, leaned her rod against the chimney next to Keefe’s, and sat down beside him on the mossy hearthstone. She rubbed her hand a few quick strokes across his back, as if trying to warm him if she had done it more vigorously. She left her hand on his shoulder and leaned lightly into his side.

“Well?” he said.

“Upstream, the pool down from where the fire road cuts above it. The big hemlock down on the far bank.”

Keefe nodded knowingly. “A few of the big ones in the back eddies there.”

Sandy nodded as well.“ Bounced my fly off the boulder to the right, couple feet above the cutaway. Got one of those big ones.”

“Wonderful. On a yellow stonefly?”

“Yeah. I took a few from your bench. I was out.” Sandy made no reference to the flawed flies, but she looked tentatively at the side of Keefe’s face, searching for a readable sign.

“Good. That’s what they’re for,” he said.

Sandy stood and stretched, arching her back. “I’m hungry. You have anything to eat back there?”

Keefe pushed himself up from the hearthstone, took his rod, and handed Sandy hers. “I think we may be able to stir up something.”

Keefe walked a half step behind Sandy as they stepped out of the clearing onto the fire road. Sandy turned immediately downstream, and as she turned, she saw from the corner of her eye that Keefe seemed to hold back, for no more than a second, and that he expelled a shallow sigh before he turned down the fire road in step with her. Any other time she’d have noticed nothing in this moment, but now, after finding the botched stoneflies on his bench, she was on the alert. Had he found his haven in the clearing, but then not known how to return to the bungalow from there? In this place he had lived for over twenty years, this place he knew so intimately, had he been lost? For now, she would say nothing, only continue to watch for the signs that might form a pattern. Sandy took Keefe’s hand, something she rarely did, and held it close as they walked the fire road back to the bungalow. Keefe’s hand firmly returned the press of her grasp.

This is an excerpt from Tim Poland’s latest novel, Yellow Stonefly, now available from Swallow Press/Ohio UP (ohioswallow.com/book/Yellow+Stonefly). Poland is also the author of The Safety of Deeper Water (Vandalia Press/West Virginia UP, 2009). His short fiction, poetry and essays have appeared widely in various literary magazines. He lives near the Blue Ridge Mountains in southwestern Virginia, where he is professor emeritus of English at Radford University.