“Cameras will always be pointed at beautiful and unusual creatures, but how much deeper can the lenses penetrate?” — David Gulden, Photographer and Environmentalist

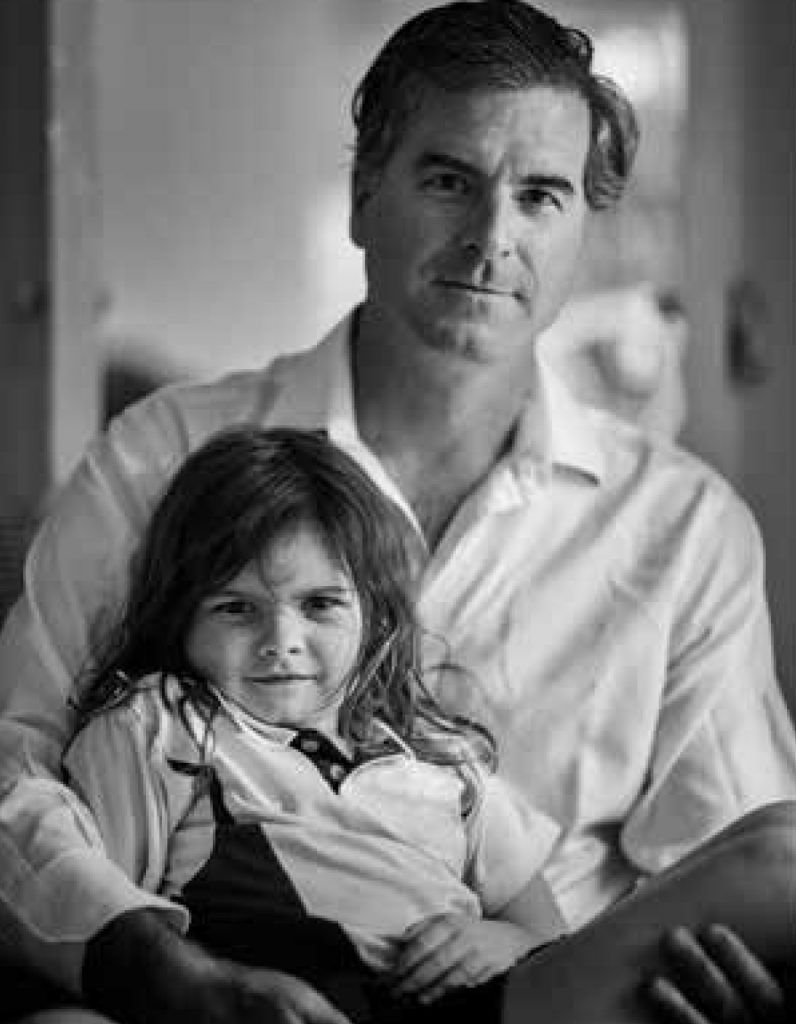

I met David Gulden in 1991, when we were freshmen at Roanoke College. Memory is fleeting, but I recall he left after a semester or two and transferred to a university in Cape Town, South Africa, where he spent plenty of time surfing. Our college didn’t let him transfer credits, so he ended up graduating from Roanoke a year later than me.

My friend enjoyed eating at the Olive Garden. I remember feasting on unlimited salad and breadsticks (we never ordered entrees) and listening to his stories about Africa. He spoke of safaris and paddling out in the shark-infested waters of Jeffreys Bay—a renowned surf spot in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. Fortunately he survived, although when you look at his published photographs and body of work, you wonder how.

“Amboseli National Park, June 11, 2016 @ 8:10AM. When an elephant shakes his head this way, it is a sign of exasperation. I suppose I was photographing him too closely for too long. This paparazzo would apologize if he could.“

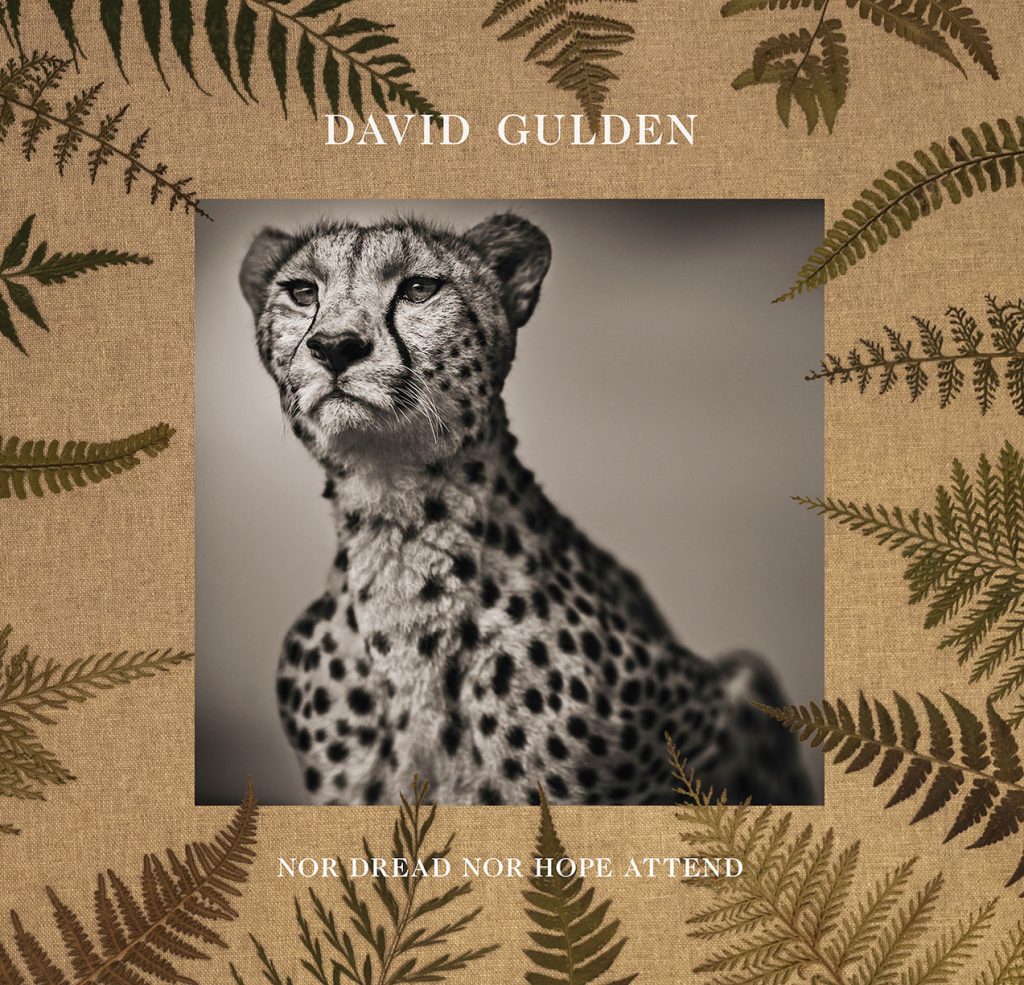

Gulden’s connection to the land and wildlife of Kenya began when he was 15 years old, when he traveled there with his father on safari. This connection grew to advocacy, and the 66 black-and-white photographs collected in his second monograph, “Nor Dread, Nor Hope Attend” (Damiani, October 2020), reflect this commitment to relaying the truth of the impacts of declining habitats—and showing the fierce beauty of the animals of the African plains and the expansive landscape itself.

The photographer’s process signals his respect for the animals and their daily lives he witnesses. Gulden presents large-format images without digital alterations, such as compositing or changes to their physical reality. When taking photos, Gulden moves as close as possible using a 50 mm lens for half the images. He trusts the natural world to deliver.

“When I photograph, I succumb to the beauty and to the science of the subject,” says Gulden. “I do not wish to create images purporting to be more beautiful than the reality being photographed. I do not try to make the old look new. I wish to show the timelessness of my subjects.”

Gulden spends a considerable amount of time in the wild, waiting and watching. He believes this patience, combined with curiosity, sets his work apart.

“As a photographer, I do not consider myself an artist. It is not art that I am making, but life that I am engaging. The only art I employ is the art of curiosity.”

The notable Kenyan paleoanthropologist and conservationist Richard E. Leakey has campaigned for years advocating mindful management of East African land. In the book’s afterword, he notes the continuing troubling trend of human and animal populations moving in opposite directions in Kenya, and the very real potential reality that the animals held within the frame of Gulden’s photographs may one day soon disappear.

“Can there be a future for wildlife under these circumstances? I am not optimistic. Environmental awareness is so much more than elephants, hedgehogs, and vultures; it’s more than national parks. The biologists, ecologists, and other scientific experts must be encouraged and facilitated in finding long-term solutions,” Leakey writes.

“Death” by W.B. Yeats

Nor dread nor hope attend

A dying animal; A man awaits his end

Dreading and hoping all;

Many times he died,

Many times rose again.

A great man in his pride

Confronting murderous men

Casts derision upon

Supersession of breath;

He knows death to the bone – Man has created death.

Gulden’s direct and pure approach to the photographic process, along with his patience to search, find and sit out these moments, all combine to offer a rich view of Kenyan wildlife. But his images are more than beautiful images from the African plains. The landscape suggested beyond the picture borders implies a bigger story, and an implication of a wider, more tangled narrative of the environment, habitat and conservation at odds.

I haven’t seen Gulden since our days at Roanoke. After college, he moved to Kenya, where he lived outside Nairobi on Hog Ranch, the one-time home of celebrated photographer, artist and adventurer Peter Beard. Gulden’s father was friends with Beard, who no doubt played an instrumental role in Gulden’s eventual development into the photographer he is today.

The natural wonder and animals of Kenya continue to inspire Gulden. Today he lives with his wife and daughters in Karen, a suburb of Nairobi named after the Danish “Out of Africa” author Karen Blixen. His studio is there in a makeshift garage, but he spends a great deal of time in the wild. He is currently at work on safari in Tsavo National Park.

“The Centre Cannot Hold” (Glitterati, 2012), Gulden’s first book of photos from the African plains, received widespread acclaim. Beard, who passed away in 2020, praised the collection as, “The best African wildlife photos yet.”

Gulden’s latest work of “concerned photography” is equally stunning and shows us what’s left of Kenya’s wilderness through the unique eye of a lensman who’s more than a photographer.

All proceeds from the book will be donated to Space for Giants, a nonprofit foundation working to secure the future of the African elephant. Learn more at www.davidgulden.com.

Joe Shields is the editor in chief of The Virginia Sportsman. He is a writer and marketing executive based in Charlottesville, Virginia. His writing and photography have appeared in The Virginia Sportsman and other publications. He is also a gallery-represented artist whose work is found in private collections and several galleries in Virginia. Whether fly fishing or surfing, drawing or painting, he celebrates sporting life and culture in his narratives and art.

Cover photo by David Gulden