Almost every day of my life, I get people asking me how to cook venison. Hunters, yes, but also the legion of people who’ve been given deer meat and have only a rough idea about how to cook it.

What follows is a comprehensive overview geared toward beginners, but with enough tips and tricks to help even long-time wild game cooks.

Let’s start with some basics. What is venison, anyway? As funny as it might sound to some of you, it’s a legit question I get asked a lot.

“Venison” is a centuries-old term that used to mean all wild game, but it has evolved nowadays to mean the meat from cervids and wild bovids: So that’s all species of deer, elk, caribou, moose, and the exotics like nilgai, blackbuck and oryx.

Pronghorn antelope, which is neither a cervid nor a bovid, also falls under the term venison. So do wild sheep and goats. Bison, wild or not, tends to not be lumped in there by some, and there aren’t enough people who’ve eaten musk ox to really put it in either box — but personally I’d call it venison.

So one thing you will notice about all these animals is that venison is red meat. Obvious to any hunter, but if you’d never actually seen venison you might not know.

VENISON AND FOOD SAFETY

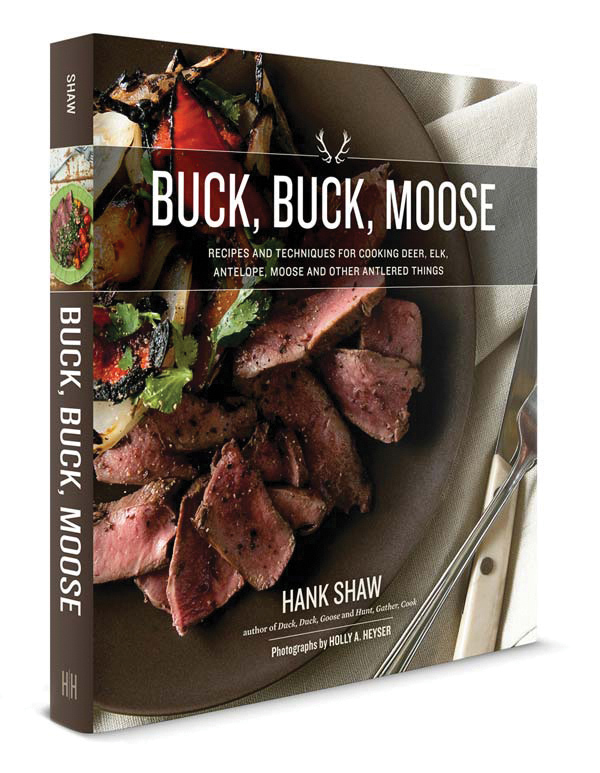

One cool thing about venison is that yes, you can eat it not only rare, but raw. While researching my venison cookbook Buck, Buck, Moose, I did an extensive search of food poisoning studies looking for cases involving venison, and I found very few over the past several decades.

It is not impossible to get a food-borne illness from raw or undercooked venison, but it is very rare. There have been a few isolated cases of listeria, likely involving poor handling of the meat, and a few of e. coli poisoning, which were linked to contact between the deer’s feces and meat that was subsequently undercooked.

Most serious but even rarer are the very few cases where eaters of raw or undercooked venison contracted toxoplasmosis. Solution? Freeze before eating rare or raw. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, freezing kills toxoplasmosis.

So once your deer meat has been frozen, you are free to make dishes like venison tartare or any backstrap recipe where you cook the meat rare.

IS VENISON HEALTHY?

Short version: Yes.

Deer meat and other forms of venison are naturally low in fat, and the fat that is there is high in omega-3 fatty acids. I wrote a full article on deer fat here, so I won’t go into the details too much here.

Exact nutrition details on wild foods is a fraught affair, since you have variation in species, size and diet. So any charts or graphs you see on other sites should be taken with a grain of salt.

Because venison is so low in fat, and because it is in general denser than farmed analogs like beef or lamb — deer, elk and such are athletes living by their wits, unlike most farm animals — venison will have more vitamins, protein and minerals than an equal weight of, say, beef.

Other than nutritional information, you should know about Chronic Wasting Disease, which can affect all cervids, so that means deer, elk, moose, caribou. Pronghorn are unaffected. I wrote a survey of the state of the research on CWD and humans in 2019, and it holds up pretty well today.

Short version: Chronic wasting disease does not affect humans. But similar prion maladies have jumped species barriers in the past, and no one wants to be Patient Zero.

HOW TO COOK VENISON: BASICS

OK, let’s look at cooking venison now.

Number one rule, the Prime Directive: You can always cook venison more. It is impossible to uncook something. This of course holds true for all things. To that end, know that because venison has so little fat — and no internal marbling — it gets hot and cools down much faster than fatty beef. Or even lean beef.

Fat is an insurance policy against inexpert cooking. Venison leaves you without that safety net, to mix metaphors. This is why it’s vital to err by cooking too little, if you are going to err. It’s also why you almost always want to start with room temperature meat.

Second rule, or rather observation: Inexperienced cooks cook the tender parts of venison (tenderloin, backstrap, flat iron steak, etc.) too much, and the tough parts too little.

Third rule, which has exceptions: The front of the animal is tougher than the back end of the animal. Let me unpack that a bit.

The front of a deer or similar creature features the shoulders, front shanks, neck, head and tongue. With the exception of the aforementioned flat iron steak, and the “whistlers” on a large animal like an elk or moose or bison (these are the long, skinny muscles that cover the animal’s trachea) every part of this requires long, slow cooking.

Even the front part of the backstrap isn’t the best part. But it will still be fairly tender. Now the hind end has the hind legs, obviously, most of the backstrap, the tenderloins and the hind shanks.

Only the hind shanks are tough and gnarly. The hind leg, separated into single muscle roasts, can be served medium-rare, and is an excellent candidate for smoking like a roast beef or tri-tip.

VENISON CUTS

OK, this one can get weird, since butchering a deer is a very personal act, as idiosyncratic as it gets. Bottom line: You butcher a deer or elk or whatever based on how you are going to eat it. Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.

I go into serious detail on how to butcher a deer in my book, and you’ll have to get a copy to get those details. (Hey, I gotta make a living somehow!)

That said, let me start with the venison cuts most people get back from a processor or butcher. Those cuts range from useful to an abomination.

Actually, most processors cut venison poorly… if it’s even your deer you get back. Yes, that can happen. Most processors are slammed with tons of animals all at the same time, especially in the Midwest where deer seasons are short and a zillion people are out hunting all at the same time. Lookin’ at you, Pennsylvania and Michigan. And the $100 to process your deer isn’t very much.

So they have their way. Not a fan. Here’s why.

Medallions of backstrap. Not inherently terrible, but way harder to cook perfectly, compared to cooking lengths of backstrap, which you then slice into medallions once cooked. That method is prettier, too, since you get to see the lovely pink interior.

Shoulder “roasts.” Um, not roasts unless you want to make venison pot roast, which is perfectly great. But don’t open up the packet thinking you can cook this medium-rare.

The Dreaded Leg “Steak.” I hate this cut with the heat of 10,000 suns. It should be outlawed. If you’re not familiar, you get this abomination when some dude with a band saw blasts through your deer’s hind leg crosswise, bone and all.

What results might at first glance look like a steak, but it’s really a half-dozen muscle groups, sliced against the grain, with a bone in the center. Those muscle groups are often just barely held together by connective tissue. So when you cook this war crime of a cut, two things happen: The weak connective tissue separates, so your “steak” falls apart, and the strong connective silverskin contracts, warping each segment of the so-called steak horribly. I could go on, but I feel my eyelids getting hot.

Finally, you will get metric buttloads of ground venison, ideally cut with the pork fat or beef fat you asked for, but sometimes not. That’s right, most processors will grind shanks, flanks, rib meat, neck and much of the shoulder. It’s just how they do things.

MY VENISON CUTS

Clearly you can see I prefer doing things myself. Here’s a rundown on the venison cuts I normally do. Again, diagrams and photos galore are in my book.

Short version: I do what’s called seam butchery. The seams are the connective tissues between muscles. All you need to do is disassemble the animal the way God assembled it. I use a pocket knife. A sharp pocket knife, but a pocket knife nonetheless.

I tell you this because many people will try to sell you weirdly specialized or incredibly expensive knives. They are not needed. You do however need whatever knife you have to be sharp. I have a whole article on deer processing tools here, if you want to get into detail.

Quarters come off first, often in the field. On small deer and pronghorn, I leave the bone-in the neck roast unless I am in a CWD area, in which case I debone it. Larger animal necks I always debone.

I keep the tongue, heart (unless I blasted it, which happens), kidneys and, on young animals, the liver. I do not keep the livers of old animals, because even though they have probably not abused theirs like I have mine, they are still very, very strong tasting.

If I am around a ranch, I use a saw and saw off ribs, especially on bovids like nilgai, bison or oryx, Their fat is tasty, not waxy, so “beef” short ribs with these animals is mad crazy delicious.

I almost always remove the backstrap and tenderloin, as opposed to cutting chops. That one’s on me. Just my own idiosyncracies. But, if you do cut chops, cut them thick, like two ribs on a deer — or cut a pretty rack. Single-bone chops should only be from large animals. No one likes a tiny chop. This is America.

All shanks get removed whole. I section large ones for ossobuco. A Sawzall introduces a certain Goodfellas fun to the party, but isn’t strictly needed.

Hind legs get separated muscle by muscle. You can do most of this with your fingers after removing the femur, which you can cross cut for marrow bones. Again, do this with bovids fer sher.

Shoulder gets kept whole on little deer for things like braised shoulder, and on large animals I will cut a flat iron steak, then use the rest for things like venison barbacoa.

VENISON COOKING METHODS

I am racking my brain trying to find a method for cooking venison that I don’t like…

…OK, found one: Poaching. The idea of a venison steak or really any red meat gently poached in wine or water is pretty revolting. But then I know the difference between poaching and braising.

I tell you this because yeah, you can pretty much do anything to cook venison cuts: Roasting, frying, grilling, smoking, braising, stewing, even, as we’ve already covered, raw.

SOME MORE TIPS:

1. Thin cuts you want to remain pink should begin cooking very cold. I will actually bread my chicken-fried venison, let it set in the fridge a while, then even freeze it for 20 minutes before cooking. That keeps the center pink while you get that golden brown. Trippy, eh? But it works.

2. Like smoke rings? And who doesn’t? Start smoking venison cold. This is because a smoke ring stops developing at around 140°F, so the longer the meat takes to get there, the better the ring.

3. Thick cuts and lengths of backstrap must start at room temperature, unless you are reverse searing. This promotes even cooking and prevents the weird black-and-blue effect that, inexplicably, some people like.

4. It Will Submit. I don’t care how old your moose was, it will get tender. Eventually. I’ve had bull elk pot roasts take 5 hours, but they eventually did get tender. Time is your friend. When in doubt, make a pot roast or braise the day before you need to impress someone.

5. Seasonings (except salt) hate high heat. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve eaten someone’s “special spice rub” that tasted like an ashtray because he (and it’s always a he) put it on the grill over a raging fire. Paprika gets especially bitter when burnt. So please, cook your backstrap with only salt and fire. Then, the moment it comes off the heat, roll it in your rub and the let it rest. You’re welcome.

6. All venison Wobbly Bits taste good grilled over a smoky fire, chopped, then served in a tortilla with salsa. Period. This is a great way to introduce people to offal. Know that if you are going to make tongue tacos, they do need to be braised tender before they hit the fire.

7. A word on venison marinades. I use them, but in a limited way because they don’t penetrate to the center of all but the thinnest cuts. But, I do use them for this, and I have a variety of venison marinades here. My all-time favorite dish that uses them? Venison arrachera tacos — yep, that’s skirt steak.

FINAL WORDS

A few final thoughts on how to cook venison. It’s a journey. I’ve been seriously cooking deer and other types of venison for more than 20 years, and I still learn things each season. Don’t beat yourself up if you mess something up.

To that end, I’ll leave you with some ideas to fix mistakes, or make use of botched attempts. First, I’ll reiterate that you can always cook something more. So most of my fixes are for overcooked things.

You made a venison sausage that didn’t bind, so when you eat it the meat crumbles? Keep it in links for now, but use it out of the casings for venison chili, or venison lasagna, or a venison ragu. All of these are good uses for ground venison with no added fat. You overcooked the backstrap? Chop it small, toss it with salsa, reheat gently and put it in tacos. Or the aforementioned chili, etc.

The roast was too tough? Keep cooking it until it falls apart. But it’s too dry! Aha! Now shred this hammered roast. Add pork lard or some other fat that makes you smile in a frying pan, let it get hot, then spread the shredded roast meat out and sear it on one side. It’s amazing over rice, in a tortilla, or in a sandwich.

I could go on, but you get the point. I hope this helps you at least a little.

Cover photo by Holly a. Heyser